Published: Jan 6, 2024 by Alistair

I recently purchased a Husqvarna Automower 305. It’s a robotic mower that can drive around the backyard cutting the grass.

Although some Automowers support a cloud connection, I specifically bought one that didn’t include internet access. The 305 has no internet, WiFi or cloud connection. This means the manufacturer can’t enforce a subscription service, the device isn’t exposed to internet wide Cyber attacks and it ended up being the cheapest option.

The down side is that I can’t communicate with the device from my Home Assistant instance.

The mower does support a BLE interface though.

Husqvarna provide an Android application which can communicate with the mower via Bluetooth. So I thought I could reverse engineer the protocol and support it in Home Assistant. That way I can use a ESPHome Bluetooth Proxy to control the mower via HomeA

Setup

Sniffing the Traffic

The first step was to sniff the Bluetooth traffic to get an idea of what was happening.

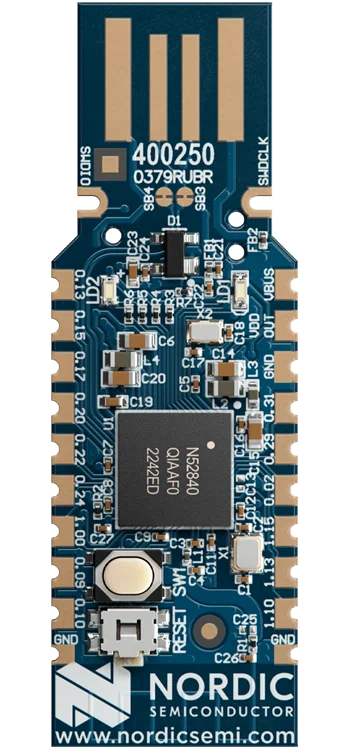

Using an nRF52840-Dongle, Wireshark and some Nordic scripts I could sniff Bluetooth packets.

So I fired up an old Android phone, installed their app, connected to the mower and made sure I could control the mower. Once I had that working I sniffed the packets with the nRF dongle.

The Android phone told me the BLE MAC address, so I could easily filter by that to see only communication with the mower.

The first thing I noticed is that Wireshark wasn’t able to decrypt the data. The Bluetooth connection was encrypted. I tried to extract the keys from the Android phone, by using ADB to get the HCI logs, but I couldn’t get it to work.

Luckily legacy Bluetooth isn’t very secure. I reset the pairings on the mower and phone and this time paired the two while Wireshark was running. Older Bluetooth protocols send the encryption key in plain text during pairing. So Wireshark could read the key and then automatically decrypt the traffic.

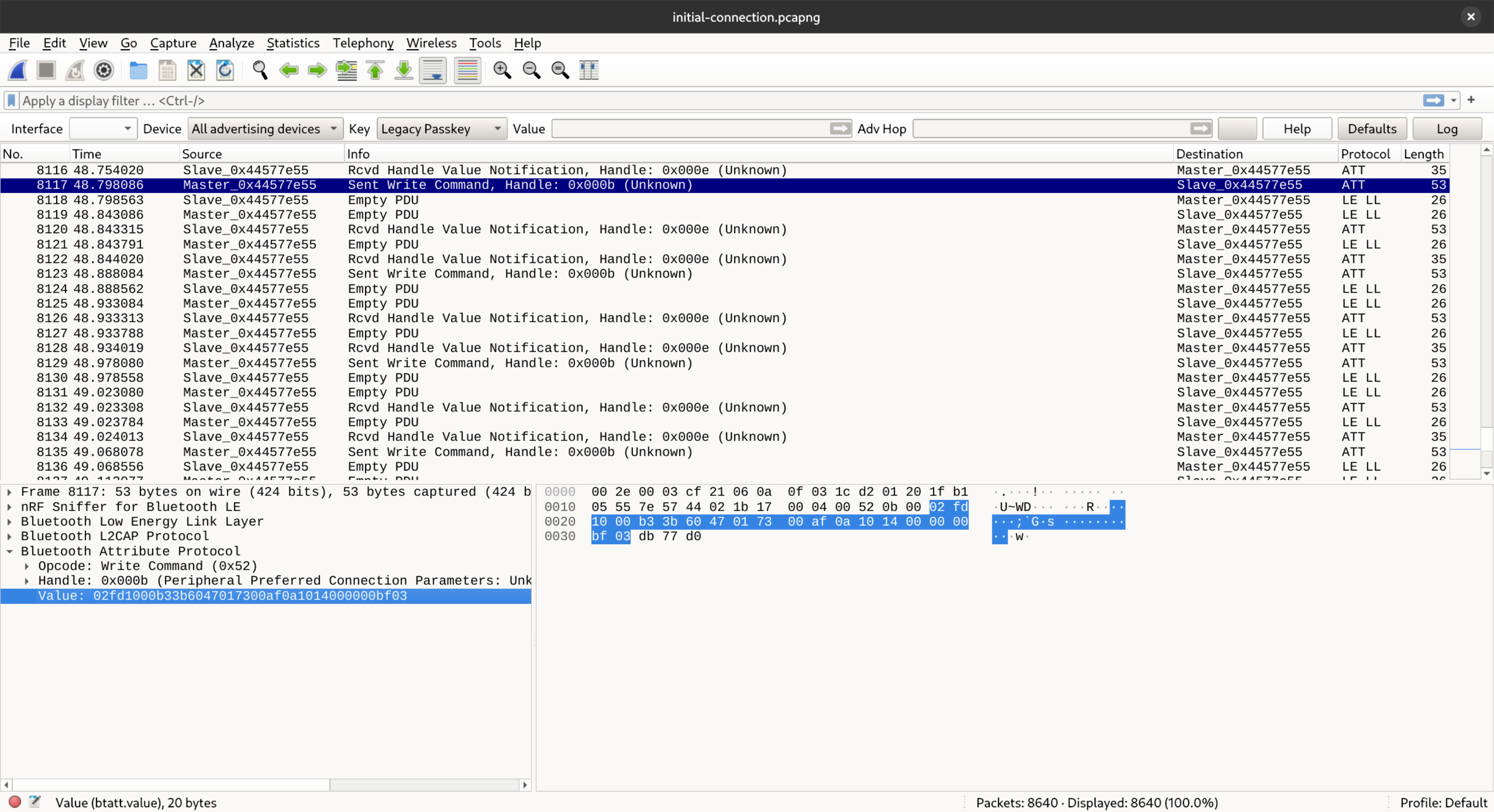

After sending a few commands from the Android application I got something like this in Wireshark.

Reading through the collected packets in Wireshark I could figure out that it was a request and response protocol, where the phone wrote something to the mower and got a response back.

I was hoping that it would be obvious how to pause and resume the mower, but there was a lot of traffic and nothing obvious jumped out. I also saw very differing length payloads, which made it hard to follow.

At this point I gave up on deciphering the packats myself and instead switched to reverse engineering the Android application.

Decompiling an Android APK

I looked around for the best way to decompile an Android APK and landed on using jadx.

jadx seemed to be recommended and easy to use. It isn’t able to recompile the decompiled code, but for me I thought that wasn’t an issue.

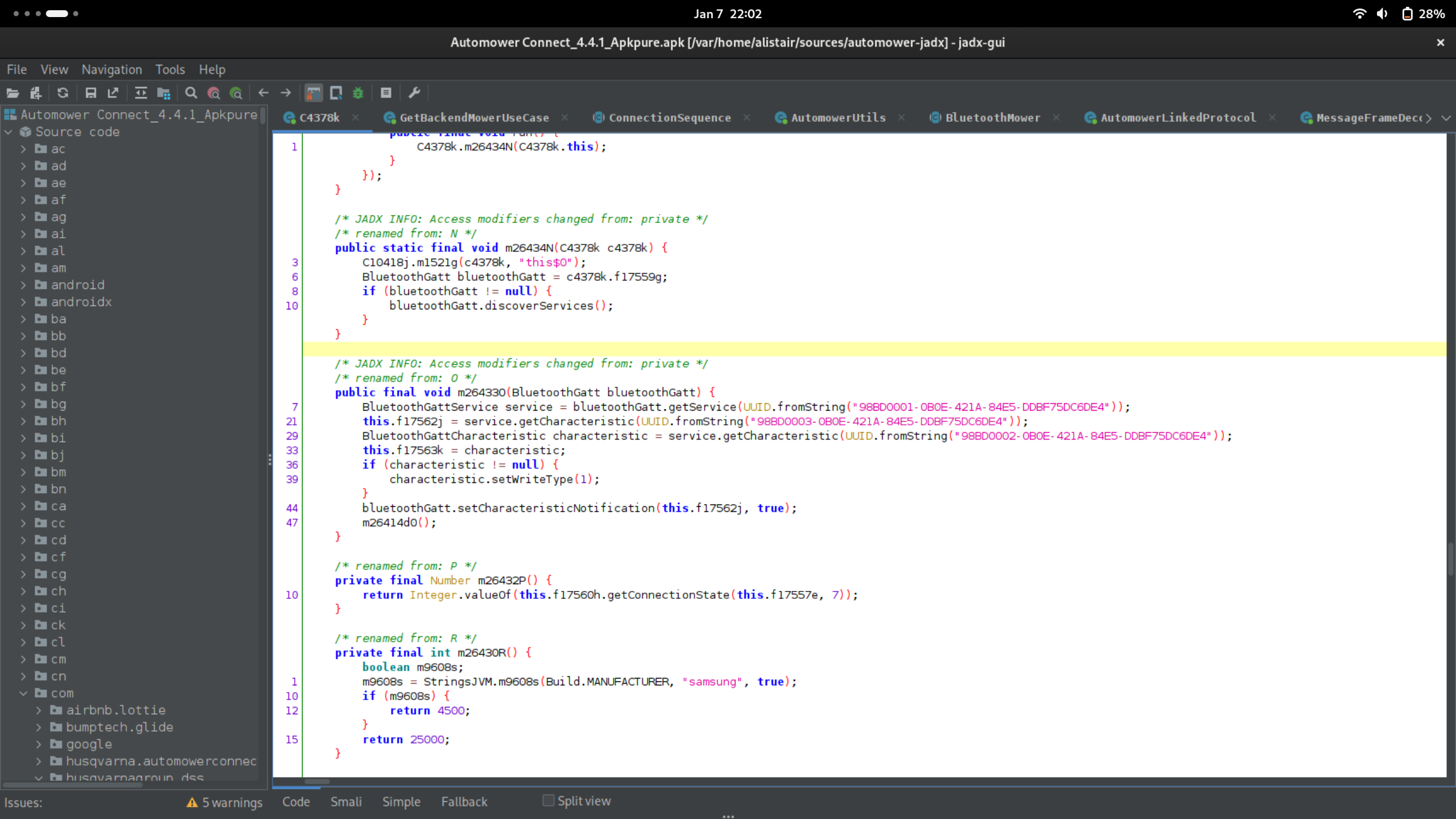

So I used jadx to decompile the APK and started digging into it. This is what jadx looks like if you haven’t used it before.

Reverse engineering the protocol

At this point I had examples of the sniffed communication commands and decompiled Java code.

Zeroth step - Preparation I didn’t do

In hind sight I wished I studied the protocol first.

Hopefully I would have determined that each packet starts with 0x02, xFD and grepped the decompiled code for that. That would have helped me easily find where the packets are constructed.

The other thing I wish I knew about at the start is the jadx deobfuscation feature.

Before running that I spent a fair bit of time digging into what I thought was a useful function. After running the deobfuscation feature I found out they were part of Timber a logging library

First Step - Finding the packet creation

After grepping around I found this (it was more confusing to read at the time before I found the deobfuscation)

public static final void m26420a0(C4378k c4378k) {

...

byte[] bArr2 = c4378k.f17564l;

C10418j.m1524d(bArr2);

byte[] bArr3 = c4378k.f17564l;

C10418j.m1524d(bArr3);

byte[] copyOfRange = Arrays.copyOfRange(bArr2, 0, Math.min(bArr3.length, c4378k.f17568p));

byte[] bArr4 = c4378k.f17564l;

C10418j.m1524d(bArr4);

Boolean bool = null;

if (bArr4.length > c4378k.f17568p) {

byte[] bArr5 = c4378k.f17564l;

C10418j.m1524d(bArr5);

int i = c4378k.f17568p;

byte[] bArr6 = c4378k.f17564l;

C10418j.m1524d(bArr6);

c4378k.f17564l = Arrays.copyOfRange(bArr5, i, bArr6.length);

} else {

c4378k.f17564l = null;

}

C10418j.m1524d(copyOfRange);

Timber.m5076h(BleDevice.m26568b(copyOfRange, "Sending", null, null, null, 14, null), new Object[0]);

BluetoothGattCharacteristic bluetoothGattCharacteristic = c4378k.f17563k;

if (bluetoothGattCharacteristic != null) {

bluetoothGattCharacteristic.setValue(copyOfRange);

}

Helpfully the logging code is still compiled into the shipped application. So I can see that this is "Sending" the copyOfRange variable.

The line

bluetoothGattCharacteristic.setValue(copyOfRange)

seems to be responsible for sending the data via BLE.

Perfect!

Following the function calls back from here I found this helpful line, that seems to be where the entire packet is generated

byte[] m26559c = AutomowerLinkedPacketRequest.m26562a().m26557e(c4371a.m26461b()).m26556f(c4371a.m26458e()).m26559c();

At this point it is just a matter of following these functions and understanding how the bytes are being appended.

Some are as simple as these

littleEndianDataOutputStream.writeByte(2);

littleEndianDataOutputStream.writeByte(253);

which are easy to line up with the payloads in the captured packets.

Some others are trickier though. A few times the code wrote a zero but the captured packets contain a non zero value.

Eventually I figured out this is because the data is modified later, by this code sequence

ByteBuffer wrap = ByteBuffer.wrap(bArr);

wrap.order(ByteOrder.LITTLE_ENDIAN);

wrap.putShort(2, (short) ((bArr.length + 2) - 4));

wrap.put(9, Crc.m46515a(bArr, 1, 8));

At this point I had a good idea of what the entire packet should look like. Some more debug logs in the code helped solve the channelID bytes, which are just randomly generated at the setup.

Although it’s difficult to read reverse engineered code as the comments, function names and local variable names are removed. It’s not impossible to decipher, especially with some logging still included in the binary.

Second step - Request commands

The last remaining part is deciphering each request command. I can now isolate the request bytes in the packet, but there are dozens of packets sent in starting a connection.

After some more grepping I figured out that commands are specified one at a time in individual files in the Android application, like this

/* compiled from: BatteryCommands.java */

/* renamed from: ki.c1 */

/* loaded from: classes2.dex */

public class C7379c1 extends C10786f {

public C7379c1() {

super(4106, 22);

m348e().m376a().add(new Parameter("remainingChargingTime", "uint32"));

}

Some have Parameters which makes it simple to determine, but lots don’t. So it’s hard to tell what each command does.

Determining Request Values

The easiest way I found to figure out the requests is just to sniff the command and then try to work backwards from there.

This is a little tricky as I need to monitor the Bluetooth pairing to get the encryption key. I never managed to get Wireshark to work otherwise, even after manually entering the key. This results in a lot of data to dig through

After recording commands at specific times, I can find the captured request in the code to confirm that it does what I expect.

Writing the Python scripts

Finally! With everything decoded I can start writing Python scripts. As I want to use this with Home Assistant eventually I started with Bleak for the BLE backend.

The Python scripts to communicate with an Automower from this reverse engineering effort are available at: https://github.com/alistair23/AutoMower-BLE